Sign up for weekly new releases, exclusive access to live debates, and Open to Debate’s educational newsletters.

- Debates

Features

Topics

Upcoming debates

-

-

-

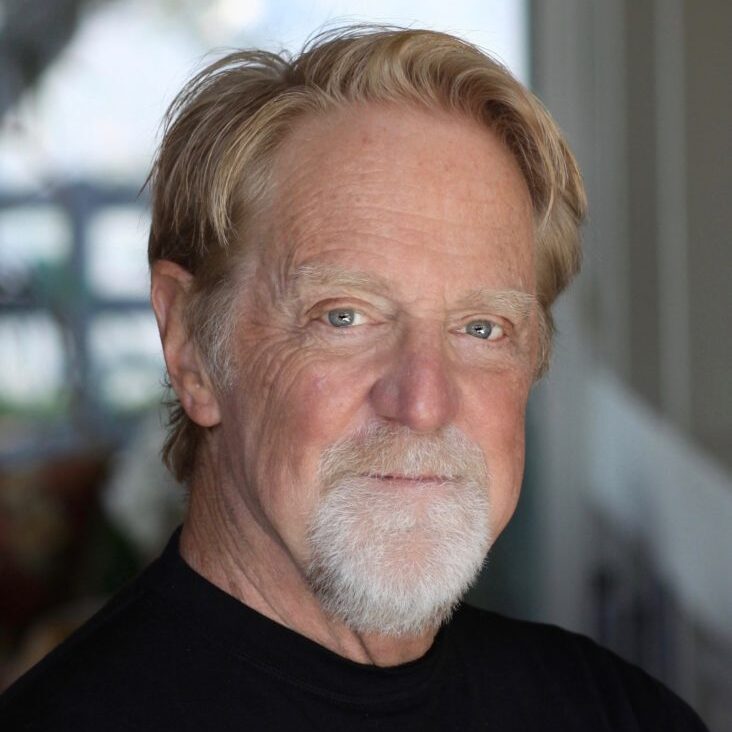

The shocking November 2022 murder of four University of Idaho students that gripped an Idaho small town and made headlines across the nation have finally reached a conclusion. The killer was sentenced to life in prison without parole and escaped the death penalty, yet there are still unanswered questions — and a lot to Think Twice about. Did new genealogy technology used in the investigation add further complications? What can this case teach law enforcement for the future? How can justice be pursued in this era of oversaturated media exposure and speculation? In this episode, John Donvan sits down with journalist Vicky Ward, who co-authored with renowned novelist James Patterson the bestselling book “The Idaho Four: An American Tragedy,” where they discuss what drew her to the case, how collaborating with Patterson changed her writing process, and how this case challenges us to reconsider elements of the criminal justice system.Friday, August 1, 2025

-

- Insights

- About

-

SUPPORT OPEN-MINDED DEBATE

Help us bring debate to communities and classrooms across the nation.

Donate

- Header Bottom

JOIN THE CONVERSATION