- Debates

Features

Topics

Upcoming debates

-

-

-

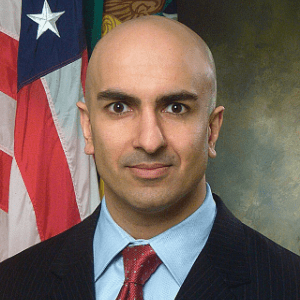

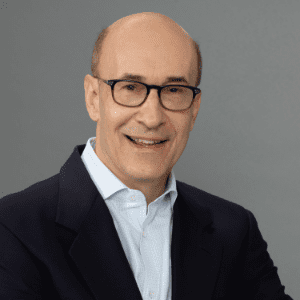

As the war between Israel and Hamas is ongoing, the nonpartisan debate series Open to Debate in partnership with the Council on Foreign Relations is taking a closer look at one proposed solution to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The two-state solution proposes a sovereign State of Palestine alongside the State of Israel and aims to address the territorial disputes, security concerns, and national aspirations of both Israelis and Palestinians. However, many have questioned whether this plan is still possible, especially during the Israel-Gaza war happening now. Those who believe it’s still possible argue that it’s the most logical path toward achieving sustainable peace and fulfilling the national self-determination rights of both Israelis and Palestinians while respecting international laws and U.N. resolutions. Those who believe it is no longer possible argue that the ongoing violence, West Bank settlement expansions, lack of trust, and failure of previous negotiation attempts such as the Oslo Accords make having both states impractical. With this critical background, we debate the question: Is the Two-State Solution Still Viable? This debate was pre-recorded as an exclusive live event on July 16, 2024, at 6 PM EST, at the Council on Foreign Relations, in New York City.Tuesday, July 16, 2024

-

- Insights

- About

-

SUPPORT OPEN-MINDED DEBATE

Help us bring debate to communities and classrooms across the nation.

Donate

- Header Bottom

JOIN THE CONVERSATION