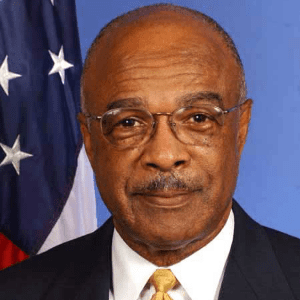

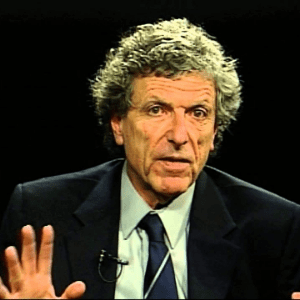

And those schools are successful. John Donvan: Larry Sand. Larry Sand: Yeah, just here in New York City, in Harlem, we have very successful charter schools like KIPP, Democracy Prep, and Harlem Success. The parents, as far as I know, there aren’t enough to keep up with the demand, yet Randi is saying that — seems to have a problem with charters. So she wants to go very slowly. It seems that the parents want these things because most of their kids are in hell holes. Now, this is not the — this is not the union’s fault that they’re in hell holes necessarily, but it’s the union’s fault because they keep them in hell holes. [applause] Kate McLaughlin: The best from a local standpoint — in Lowell, Massachusetts, it’s quite the opposite. They are actually closing the — they actually force — they wanted to close the charter school. And we actually appealed on their behalf, so they have to cut the school in half and stop teaching middle schoolers, and we will absorb those students back in the local — Larry Sand: You’re saying that the union stood up for the charter school? Kate McLaughlin: And the — the school system. But what you don’t know — again, you say, oh, teachers are against charter schools. You’re making up the story why — [talking simultaneously] Kate McLaughlin: — I am. Let me tell you why I am. Larry Sand: They — actually, they’re not saying that. They are saying teachers unions use political power — [talking simultaneously] Larry Sand: — use political power to stop the proliferation of — [talking simultaneously] Kate McLaughlin: No, listen to — Rod Paige: With a teacher’s — Kate McLaughlin: From a — Rod Paige: With a teacher union. John Donvan: Rod Paige, I want to let Kate finish. Kate McLaughlin: From a local standpoint, we–from this charter school that was going to be announced–got students back from this charter school which we welcomed. We don’t get the funding for them for another year. So when the teachers unions bring up this issue, we’re somehow against charter schools. There are major issues about the funding that comes with it. But when we speak it up, we’re somehow obstructionist. That is not the case. The other issue about charter schools for me and for my type offers union is it’s an equity issue. And my teachers union president has gone even to the governor and suggested that if charter schools are truly innovative, they should be a draft and not a cream of the crop selection. Larry Sand: They are not the cream of the crop — [applause] Kate McLaughlin: And that — and it is a total equity issue because we’ve all agreed that achievement gaps come from school-based issues. They come from social issues, and they come from economic issues. And if you alone base a lottery on which parents have gone to sign up, you have already changed some of those issues. So it is an equity issue. John Donvan: To the other side, Larry Sand. Larry Sand: Go see Bob Bowden’s film. You tell me those parents and those kids are the cream. These are poor people. Maybe they’re the cream of the poor people. I don’t know. [laughter] John Donvan: Let’s bring this back to the issue of unions. And I want to go to the side that is arguing that teachers unions are to be blamed for the failure of the schools. And the other side, your opponents are arguing — two of your opponents used in their arguments the point that there is no real correlation between states that have strong teachers unions and poor academic achievement. Kate McLaughlin, your opponent said there is absolutely no research on that. And Randi Weingarten pointed to the numbers of states where actually there were strong unions and strong school results. I’d like one of you to respond to that. Terry Moe: I’d be happy to respond, but I don’t know where this stuff comes from, really. Look, many, many, many, many factors influence student achievement. And to say basically that schools in the South don’t do as well as schools in the North, which is true, and that schools in the South don’t have unions and the schools in the North do, and to say, gee whiz, it must be because unions are good for schools. I — don’t try that at a university. It doesn’t wash. [applause] Terry Moe: So, look, as far as the research goes, I don’t know where Kate’s getting this. I mean, there is a research literature. Actually, it’s pretty big on the impact of collective bargaining on student achievement. She says there’s nothing. There is, plenty. It started sort of back in the 1980s. Most of the literature I think is not good. But that’s typical of most of social science. A lot of this stuff is bad. And part of the reason is that things are complicated. It’s very hard to do good studies. So you can’t just like count up studies. The results in this literature are pretty mixed. And I think it’s partly because, A, it’s complicated, and B, a lot of the studies don’t do it very well. But there are two studies that are actually in very top-level journals, they have been through very rigorous peer review process. They are one by Caroline Hoxby in the “Quarterly Journal of Economics,” 1996. Another one is by me in — [laughter] John Donvan: But that one’s really good. Terry Moe: Yeah, this — it’s a lot better than Caroline’s. And it is in the “American Journal of Political Science,” 2009. Both these studies show, through a quantitative analysis, both of them very extensive, that the impact of collective bargaining on student achievement is negative. John Donvan: Okay. Randi Weingarten, teachers union president. Randi Weingarten: So, Terry, you’ve actually just made the point that I think many of us are trying to make on this side, which is it is complicated. There is not one factor that either causes student success or — or is an obstacle to it. And that’s exactly what we are trying to say. So ultimately, just like we did not say that teacher unions were the reason why Maryland or Massachusetts or New York were so successful — and by the way, that was just in quality counts from education week. We were not the ones that said that Finland or Japan were most successful. We’re just saying that those are the correlations. Now, there is one person who used to actually agree with you hugely Diane Ravitch who, in looking at much of the evidence over the course of time, whether it was on charters or whether it was on vouchers has thrill just written a book saying slow down. The evidence of these kinds of market strategies just doesn’t work. My point is this: Whether you look at — everyone is going to find anecdotes to fit into their case. That’s not going to help one more child learn. We are searching for what actually works. So regardless of the quotes when they hurl at me from the NEA or from other places, I stand by the record that we have in turning around schools in New York City. Mr. Rudy Crew, who is sitting there, and I, together did probably the most important reform strategy in New York in the late 1990s, early 2000, where we actually turned around schools in Harlem. We turned around schools in New York City. We want to make sure every single child has a choice. Once they have a choice for a charter, so be it. But every child should have a choice for a neighborhood high school or a neighborhood school. And Larry, last point to you, which is this: Just recently, unlike what you said about LA, in LA, there were 36 schools that were put up for grabs by the LA school board. The charters love this. They wanted this competition. And in that competition, regular school teachers, supported by their union, won 29 of the 36 schools because of their plans. The bottom line is we need to do the things that Gary and Kate talked about in terms of helping all kids, well prepared and supported teachers, real engaged curriculum, safe and orderly environments which is what we see in charter schools all the time, good, good management that works together. And at the end of the day, if we have to find ways, as I said in 2004, to police our own profession, fire teachers that are not making the grade, we want to do that. That’s who this teachers union is. John Donvan: Okay, I want — Randi Weingarten: We want the best and the brightest for all of our young people in this country. John Donvan: All right, Randi, I gave you quite a long run with that. Randi Weingarten: Sorry. [applause] John Donvan: And I want — Randi Weingarten: Sorry. John Donvan: That’s all right, but I do want to urge us to stay as close as possible to our motions. And I think all of us probably share a sense that we want things to improve. But I want to discourage too much grand-standing on the point because we really want to get to the issue at hand. [applause] John Donvan: I want to go to the audience. That’s not to say that any of us disagree with that. Just the nature of the debate. I want to go to the audience for questions now. And what we will do is have microphones circulate in the aisles. And if you raise your hands and identify you, please stand, and I’ll bring a microphone to you. Hold it about a fist’s distance away from your mouth so that the radio audience can hear you. And I want to urge to you actually ask questions and to try to move this debate along in the area in which we are talking and not to make grand-standing speeches or to debate the debaters. They are here to debate each other, I hope prompted by you. And there’s a gentleman, a person with eyeglasses there getting the microphone now. If you could just rise, sir, and identify yourself. Audience Member: Well, I make two — two sentences. John Donvan: I would rather that you just make one statement and go to a question. Audience Member: Yes, okay. You don’t have problem with having a good car.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION